It’s hard to describe the emotion of that moment when something new pops up, in a long and slow search for information from 100+ years ago; but, use your imagination.

The initial thrill is always slightly tempered by the knowledge (or at least suspicion) that many of these articles were written by someone in the press office promoting an upcoming film, and may have had little input from the man himself; still, when an interview with Rupert turns up, including a bit of background on his career up to that point (also hard to verify), I do get a little excited.

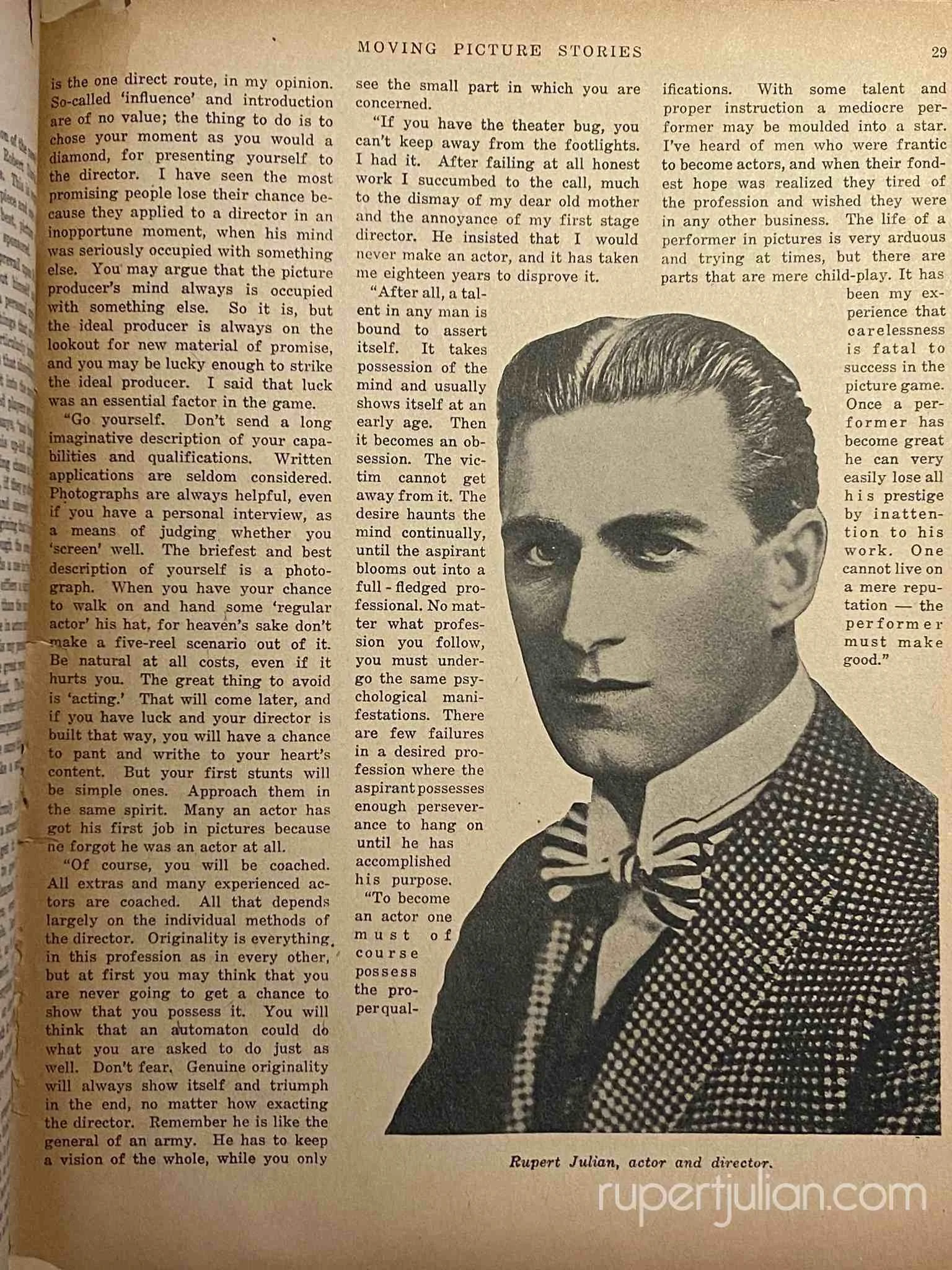

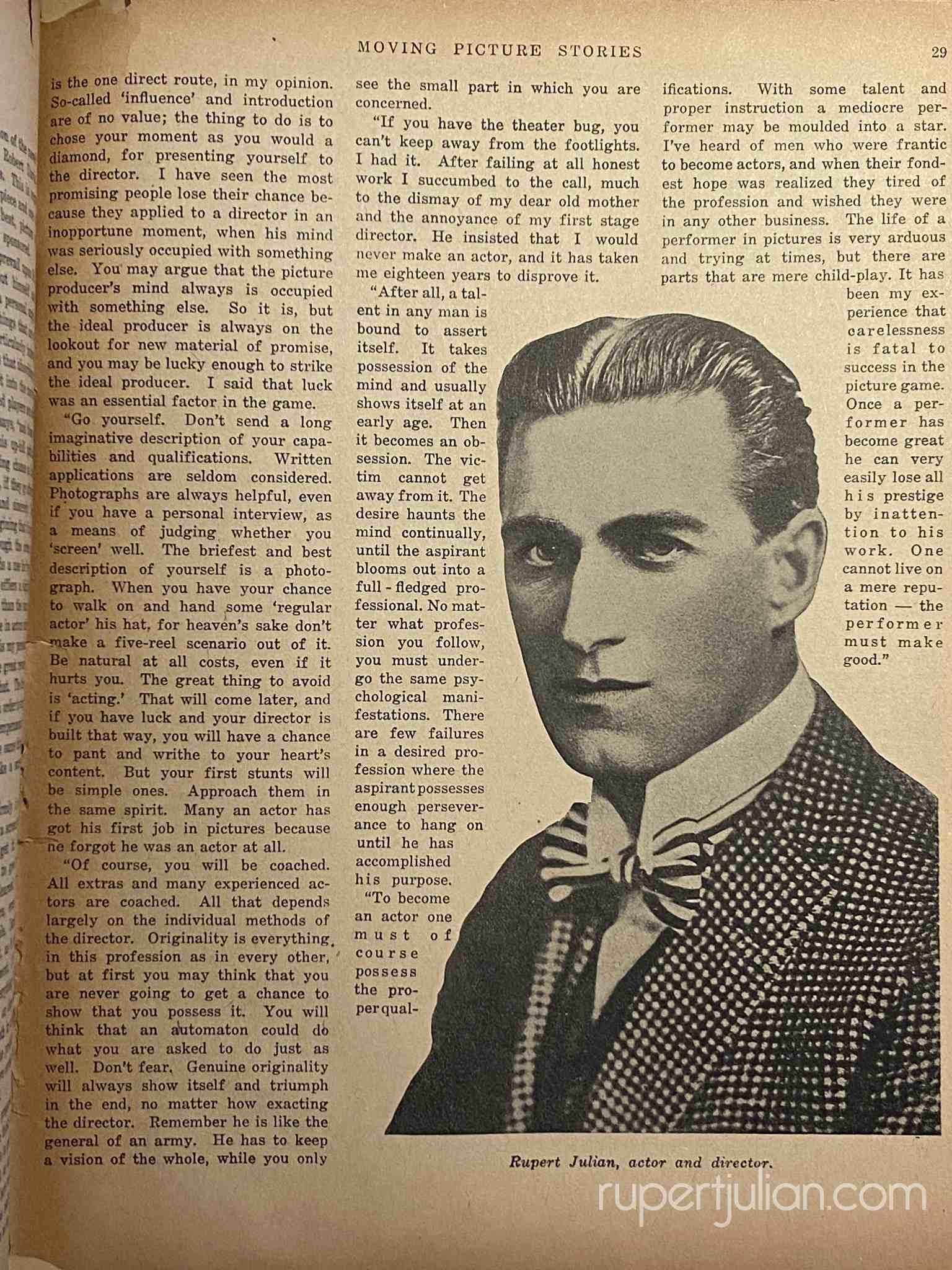

So, here is my latest acquisition: a copy of Moving Picture Stories from 1917, with a two-page article—featuring a photo I’ve never seen—with Rupert’s words of advice about getting into the movie business. He’d only been there for three years at this point, of course! But Hollywood as a whole was still fairly young in those days, so that made him practically a veteran.

I’ve transcribed the article, and included photos of both pages so you can see his extraordinary combination of striped bow tie and checked jacket—we can only imagine what they might have looked like in colour, of course…!

HOW TO GET INTO PICTURES

“To the average beginner the motion picture business holds out abundant promises of glory and easy money. In reality it is a hard uphill fight, bounded on all sides by failure and heart-breaking reverses. It takes a great deal of courage, luck and perseverance to succeed."

So speaks Rupert Julian of the profession in which he has made a distinguished reputation. He is one of the most modest of men, so he probably does not realize that he is describing his own qualities. He has had an eventful career, in the course of which he has been a sailor before the mast, a tea salesman, the engineer of a donkey engine and a gold prospector in Australia. Between each of these episodes in his life he has tried the stage, having appeared with many of the principal English actors—Sir Herbert Tree, Lewis Waller and Sir George Alexander among others. His last engagement was with Tyrone Power in the production in which he played Marc Antony to Mr. Power's Brutus.

Moving Picture Stories, 5 Jan 1917

Julian was born in New Zealand, the son of a well-to-do sheep and cattle ranchman. He received an education to fit him for the Roman Catholic priesthood, but he had other ideas and, against the wishes of his parents, he decided to follow them. The spirit of adventure was in his blood and would not be denied. When the Boer War broke out Julian immediately volunteered for active service, and for two years he saw all the hardships and realities of war. Twice he was captured by the Boers. The first time he was lucky enough to be exchanged, and the second time he managed to escape. For three days he wandered through an almost desert country without food. At last he made his way to the coast and shipped on a sailing vessel as an able seaman. He was landed at Gibraltar, but he returned again to South Africa as soon as possible and remained with the colors until two months before the end of the war, when he was invalided home, the proud possessor of a lieutenant's commission. Mr. Julian has offered his services to his country in the present struggle, but so far has not been called upon.

He endorses the saying that one finds a use for any piece of knowledge in motion pictures. His military experience has been invaluable to him, and he has often been complimented on the accuracy of his military maneuvers since he has been directing photoplays. His engagement in pictures followed an introduction to the Smalleys, with whom his first work for the screen was done. He was induced, rather against his will, to try working for the screen, but, contrary to his expectation, he found it fascinating, and when the call to return to the stage went out that fall, Mr. Julian ignored it and remained in California, a devotee of the silent drama. Lois Weber is of the opinion that no better "villain" of the smooth society type exists than that which Mr. Julian has so often played for her. He had important roles in such successes as "Scandal" and "The Dumb Girl of Portici."

But the directing bee was firmly fixed in his bonnet, and once that insect begins to buzz in a man's brain, he won't be happy till he gets a job as director. It has always been the Universal policy to advance such of its players as seemed to show talent to the position of director, rather than give the opportunities to new producers from the outside. Julian was given his chance, and he so much more than made good that he was engaged by Bluebird to produce for them exclusively, and is now regarded as one of the cleverest of directors. Four successes stand to his credit with this organization. The first, a dramatization of Tennyson's "Maud," which was rechristened "Naked Hearts;" a screen version of "L'Abbe Constantin," called "Bettina Loved a Soldiers;" another of an Emile Gaboriau story, called, on the screen, "The Evil Women Do," and his final picture, which will shortly be released, "The Bugler of Algiers," an adaptation of the novel "We Are French," by Robert Davis, the editor of Munsey's. This is regarded as Julian's masterpiece and one of the best, if not the best, picture which Bluebird has ever sponsored.

When one can prevail upon Mr. Julian to talk about himself and his profession from a personal angle, one is sure to hear things that are worth while. He is particularly interesting when he discusses that absorbing question, "How to get into the movies."

"Really talented players are always in demand," he says, "and those who decide to try this up-hill path have as good a sporting chance as in any other profession, if they go after success seriously and sincerely. There is no use in imagining that it is going to be easy, though the screen, per-haps, which finds a use for 'types' as well as actors, offers a slightly better opportunity than the stage. Personally, I believe in actors rather than types, but that is my personal preference. There are great rewards there is no denying that. The three things most required in order to win them are steadfastness, temperament and brains—just about the same things that one requires to make a success of anything you see.

"I believe firmly in all possible preparation for a screen career, if you have time to get it. Undoubtedly there are aids to good performance which may be learned. Any sort of stage experience, even carrying a spear, is valuable. Dancing is especially important, as it improves the player's deportment. I have found, myself, that everything I have ever learned or seen or done has been a help to me, both in acting for the screen and in the production of pictures. And I have certainly seen and done a good deal.

"After having prepared himself in every way he can think of, the applicant's next step is to get engaged by hook or by crook as an extra in a studio. I think I have never heard of any one who was really successful who did not begin as an "extra." It is the one direct route, in my opinion. So-called 'influence' and introduction are of no value; the thing to do is to chose your moment as you would a diamond, for presenting yourself to the director. I have seen the most promising people lose their chance because they applied to a director in an inopportune moment, when his mind was seriously occupied with something else. You may argue that the picture producer's mind always is occupied with something else. So it is, but the ideal producer is always on the lookout for new material of promise, and you may be lucky enough to strike the ideal producer. I said that luck was an essential factor in the game.

Moving Picture Stories, 5 Jan 1917

"Go yourself. Don't send a long imaginative description of your capabilities and qualifications. Written applications are seldom considered. Photographs are always helpful, even if you have a personal interview, as a means of judging whether you 'screen' well. The briefest and best description of yourself is a photograph. When you have your chance to walk on and hand some 'regular actor' his hat, for heaven's sake don't make a five-reel scenario out of it. Be natural at all costs, even if it hurts you. The great thing to avoid is 'acting.' That will come later, and if you have luck and your director is built that way, you will have a chance to pant and writhe to your heart's content. But your first stunts will be simple ones. Approach them in the same spirit. Many an actor has got his first job in pictures because he forgot he was an actor at all.

"Of course, you will be coached. All extras and many experienced actors are coached. All that depends largely on the individual methods of the director. Originality is everything. in this profession as in every other, but at first you may think that you are never going to get a chance to show that you possess it. You will think that an automaton could do what you are asked to do just as well. Don't fear. Genuine originality will always show itself and triumph in the end, no matter how exacting the director. Remember he is like the general of an army. He has to keep a vision of the whole, while you only see the small part in which you are concerned.

"If you have the theater bug, you can't keep away from the footlights. I had it. After failing at all honest work I succumbed to the call, much to the dismay of my dear old mother and the annoyance of my first stage director. He insisted that I would never make an actor, and it has taken me eighteen years to disprove it.

"After all, a talent in any man is bound to assert itself. It takes possession of the mind and usually shows itself at an early age. Then it becomes an obsession. The victim cannot get away from it. The desire haunts the mind continually, until the aspirant blooms out into a full - fledged professional. No matter what profession you follow, you must undergo the same psychological manifestations. There are few failures in a desired profession where the aspirant possesses enough perseverance to hang on until he has accomplished his purpose.

"To become an actor one must of course possess the proper qualifications. With some talent and proper instruction a mediocre performer may be moulded into a star. I've heard of men who were frantic to become actors, and when their fondest hope was realized they tired of the profession and wished they were in any other business. The life of a performer in pictures is very arduous and trying at times, but there are parts that are mere child-play. It has been my experience that carelessness is fatal to success in the picture game. Once a performer has become great he can very easily lose all his prestige by inattention to his work. One cannot live on a mere reputation—the performer must make good."

At the risk of stating the obvious, if you enjoyed this, you might quite like Rupert’s 1921 book about himself—The Man And His Art—which I’ve also photographed and transcribed here.