I came across a quote from this article when someone updated Elsie Jane Wilson’s Wikipedia page recently, and set out to find a copy of it if I could. I wasn’t expecting to find a photo of Elsie herself in full director’s gear (or ‘working togs’), though!

To be honest, I’ve focussed more on Rupert’s work on this site because he was the one I first heard about, who piqued my interest initially because I was living in New Zealand at the time (and we seemed to share a birthday, give or take 90 years or so, too).

But over time I’ve learned more about Elsie and her career, and with some new research & work around early women filmmakers from the silent era in recent years there’s been more and more info out there about her and her contemporaries. Plus, I live in Sydney now, where she was born and grew up—I believe—so I’ve often wondered if I might find out more about her here than I had been able to previously.

The quote I saw was this—

“Elsie Jane Wilson has been on the stage since she was two years old. ”I appeared in the famous English Christmas Pantomimes every year, too,” she said. “All of which was the best possible training for the pictures.””

Which I’d really love to be able to confirm! But I haven’t found her in any programmes I could see, and while I know she had a sister named Nellie Wilson, who also performed with JC Williamson companies for many years, I don’t know anything about her parents, or whether they were stage people themselves in some way.

It’s hard to imagine as a two-year-old she’d have been going to auditions on her own, so I suspect someone must have led her to that path—but…who?

I also found this interesting—

“Mr. Julian and I always appeared together until after we came to this country,” she said. “Here, we found that managers do not want husbands and wives to play opposite each other, so we were separated almost at once. When I was on the road in ‘Everywoman’ I didn’t see Mr. Julian for almost two years.”

So, now I have to find out about that Everywoman tour, too…as is so often the case, research leads to more research.

The article is somewhat hilariously dated in tone, but still an interesting read; and I’ve transcribed it below if the images aren’t big enough to read. Enjoy!

"Lights! Camera! Quiet! Ready! Shoot!"

By Frances Denton, Photoplay (1917)

(Courtesy of the Media History Digital Library and The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York)

ARE we going back to the time when women ran the civil government, the army, the men, and everything else that needed running? Back to the time when the first "Equal rights for men" advocate was accused of being un-masculine and told, in no unmistakable terms, "Man's place is the home"?

We are—perhaps. And then, again, maybe we are not. It is just possible that what looks like a cut-back to those Chinese-Babylonian-Frankish days may, in reality, be an entirely new scene which serves to introduce another reel—the millenium.

In that new story, says the prophecy, there will be no question as to whether some particular work belongs more to a man than to a woman, but each will do whatever he or she can do the best. Also, those who were good shall be happy—we have Kipling's word for it.

But whether "The Cause" is working toward Man—the Slave, or Woman—the Partner, it gained its greatest victory when Universal City gave women a chance to become moving-picture directors. Greatest because, while other victories were founded, to some extent at least, on precedent, this victory was against all precedent. Following stage traditions, moving-picture directing was considered a work exclusively the property of men. And it is a fitting thing that this city, which has given women such perfect business equality with men, should be named Universal.

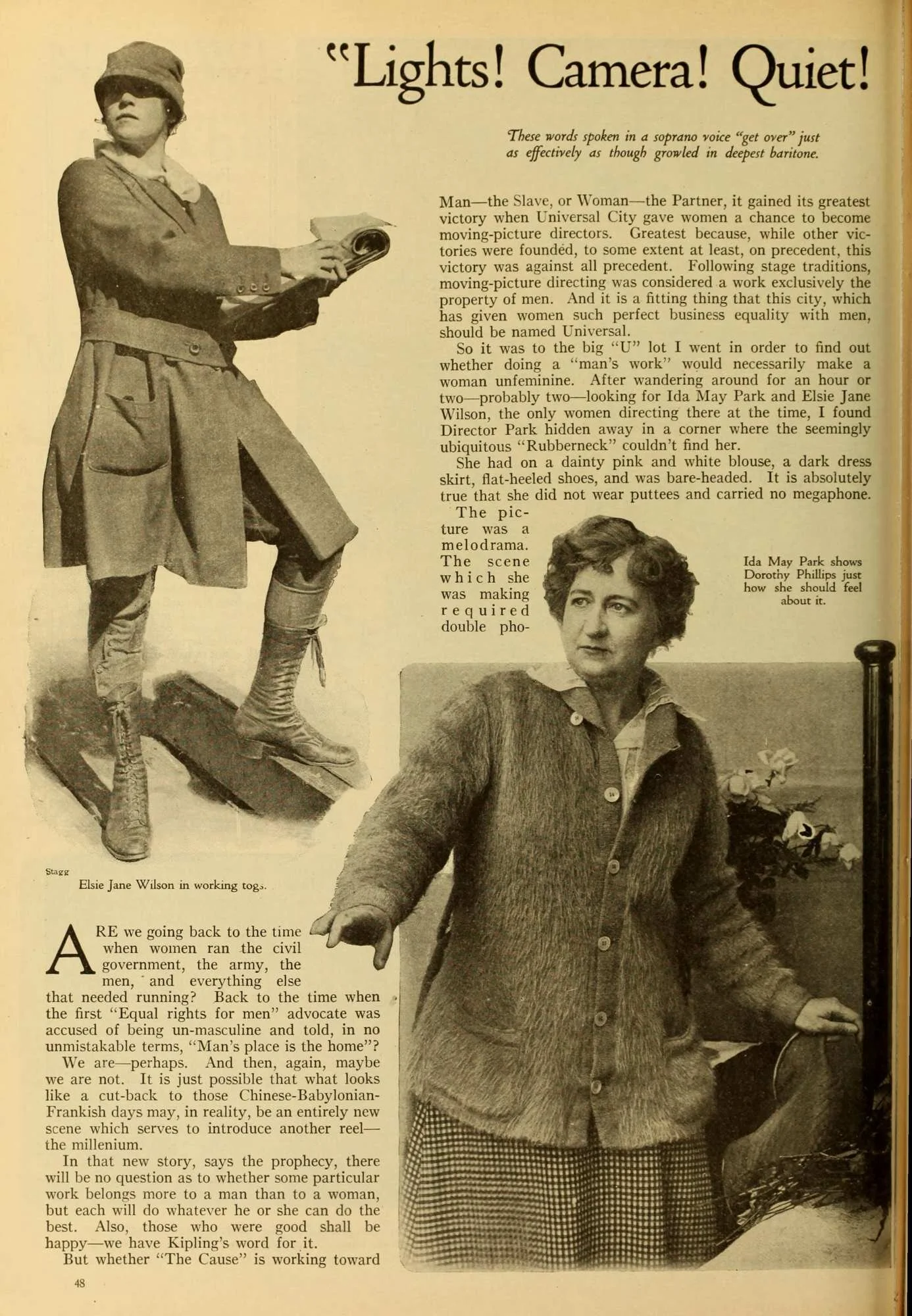

So it was to the big "U" lot I went in order to find out whether doing a "man's work" would necessarily make a woman unfeminine. After wandering around for an hour or two—probably two—looking for Ida May Park and Elsie Jane Wilson, the only women directing there at the time, I found Director Park hidden away in a corner where the seemingly ubiquitous "Rubberneck" couldn't find her.

She had on a dainty pink and white blouse, a dark dress skirt, flat-heeled shoes, and was bare-headed. It is absolutely true that she did not wear puttees and carried no megaphone.

The picture was a melodrama.

The Scene required double photography and was taking place to counts. For instance, while the cameraman counted slowly "1—2—3—4," she explained to the player just what gesture was to be made at each count—("At 67, smile. Take time to let it grow into a laugh. At 72, you are laughing.")

She was working under an overhead light on a canvas-covered stage and the sun was certainly "doing its darndest." If you have ever been in the projection room of a moving-picture theatre on a hot day, you know something about heat. This stage was hot in just that way, and the scene, which required less than five minutes to shoot, was rehearsed for three hours. And at the end of that time the director looked as cool and quiet as if she had been sitting under a shade tree with a pitcher of lemonade. She gave the impression that she could have stood there and directed that one scene all day without feeling the least annoyed, which shows that a woman can sometimes bring more patience to her work than can a man. At least, a temperamental man, and many men are temperamental.

"It was because directing seemed so utterly unsuited to a woman," said Director Park, while her cameraman was getting his titles, "that I refused the first company offered me. I don't know why I looked at it in that way, either. A woman can bring to this work splendid enthusiasm and imagination; a natural love of detail and an intuitive knowledge of character. All of these are supposed to be ‘feminine’ traits, and yet they are all necessary to the successful director. Of course, in order to put on a picture, a woman must have broadness of viewpoint, a sense of humor, and firmness of character—there are times when every director must be something of a martinet—but these characteristics are necessary, to balance the others."

It has been said that a woman worries over, loves, and works for, her convictions exactly as though they were her children. Consequently, her greatest danger is in taking them and herself too seriously.

"Directing is a recreation to me," Ida May Park went on, "and I want my people to do good work because of their regard for me and not because I browbeat them into it."

She directs quietly, occasionally taking the actor's place and demonstrating exactly how she wants a thing done, but more often explaining the situation and letting the player go through it in his own way.

"I believe in choosing distinct types and then seeing that the actor puts his own personality into his part, instead of making every part in a picture reflect my personality," she said.

Ida May Park—(Mrs. Joseph De Grasse)— has never appeared on the screen, but she went on the stage when she was fifteen years old. Her first manager was Leonard Grover, the man who brought out Mary Anderson.

"I remember that I tried to make myself look as old as possible," she said; "Mr. Grover told me that Mary Anderson had done exactly the same thing. Probably that is why I got the job."

After her marriage, she and her husband went on tour with their own company. Joseph De Grasse joined the Pathé as leading man, Ida May Park became a scenario writer. Since then she has written over five hundred successful scenarios, among them "Hell Morgan's Girl," "The Rescue" and "Bondage." She began co-directing with her husband at Universal City two years ago, and was given her own company in January of this year.

"Being perfectly normal, I don't like housework," she said. She has one other recreation besides directing—that is, caring for her roses. She has a rose garden that is remarkable, even in Hollywood.

She also said that, in her opinion, many directors of the future will be chosen from among the scenario writers of today.

Leaving her set, I walked down the big stage, past a child's blue and white bedroom, a log-cabin room, a ballroom, and a New York tenement-room, until the strains of a slow waltz led me to a living-room exquisitely furnished in red and gold. Three very blasé-looking musicians were playing this sad music while a young woman with big blue eyes, very fair skin, and very red hair, was directing some "sob stuff."

She was all in white, except for her dainty black French-heeled shoes. Also, she wore a broad-brimmed hat and white silk gloves as a protection against the sun.

She repeated my question.

"Is directing a man's work?—I should say it is!" Very carefully she drew down the top of one silk glove, disclosing a forearm plentifully sprinkled with freckles.

"Look at that!" said Director E. J. Wilson, and added, "Oh, my dear, you can't imagine the money I've spent this summer on freckle cream!" In that exclamation she expressed all a woman's natural horror of freckles, intensified by the ingrained habit every actress has of taking care of her skin. Elsie Jane Wilson has been on the stage since she was two years old.

"I appeared in the famous English Christmas Pantomimes every year, too," she said. "All of which was the best possible training for the pictures."

She came to the United States five years ago with her husband, Rupert Julian.

"Mr. Julian and I always appeared together until after we came to this country," she said. "Here, we found that managers do not want husbands and wives to play opposite each other, so we were separated almost at once. When I was on the road in 'Everywoman' I didn't see Mr. Julian for almost two years."

During a portion of this time Rupert Julian was leading man for Lois Weber and Philip Smalley.

After a brief stock engagement at The Little Theatre in Los Angeles, Elsie Jane Wilson "went into the movies" and began acting under her husband's direction. Later she co-directed with him, at the same time playing leading parts in his pictures.

"We like the same kind of pictures," she remarked, "but we have such different ideas of how to get the same effects that if we ever talked over our work we'd fight all the time."

Her assistant interrupted: "If you're ready, Mrs. Julian, we are," and she turned her attention to the set.

She was putting on a heart-interest story, the plot of which centered around three lonely old men and a little girl they had adopted and learned to love very dearly. Not a particularly original theme, but one warranted to be good for many sobs and much laughter if well handled. It had been well handled in the scenario and certainly seemed to be well handled in the direction.

"A little sad music here, please," said Director Wilson. Then to her company, "All ready, everybody? Music, camera, GO!"

The day seemed, if possible, to have grown warmer. Besides this and the usual frequent pauses made in order to work out some important detail, there were innumerable little things to distract one's attention, and yet the scene gripped and rang true. Standing a little to the side of the camera, she went through a modified form of the action in front of the player while the scene was being shot. She was "working up" her people; "putting over" the spirit of the story exactly as though she were on the stage, and in doing so she was spending her energy unmercifully. Unfeminine? Hardly! Nor is there anything unfeminine about Lois Weber. "Mother" Lule Warrenton, Ruth Stonehouse and "Peggy" Baldwin are other women who have been given companies in the past. And so, which is it to be? "Man—the Slave," or, "Woman—the Partner"?

Everything points to "Woman—the Partner."